Android is a great OS - there's no doubt about that, even if you measure that statement using the number of active installations. It has an interesting history, starting from plans to create an OS for digital cameras and ending up being Google's core mobile platform running on around a billion devices. It is technically well designed, open source and very adaptable; from CPU architectures to screen sizes, Android can adapt.

|

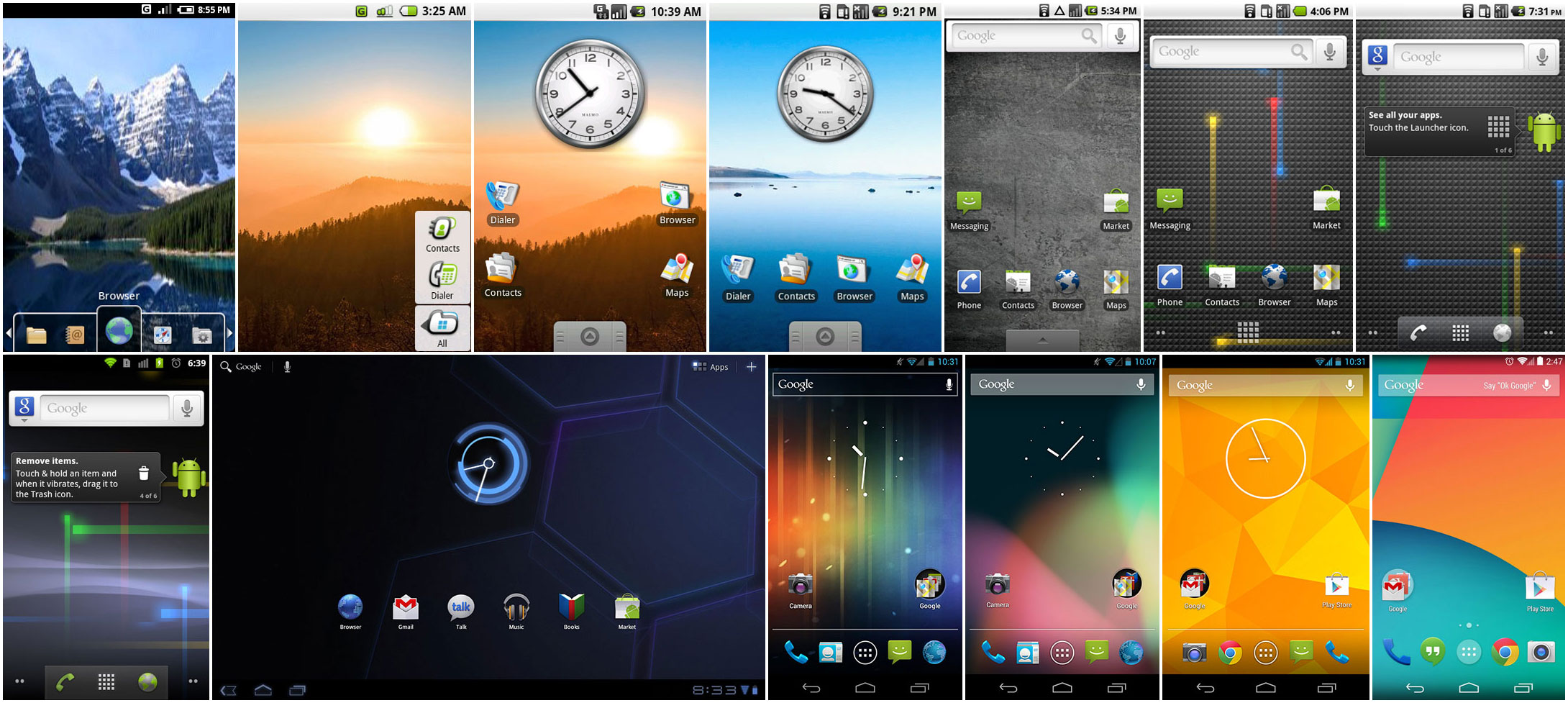

| Progress of Android over the years (Ars Technica) |

As Android progressed to meet the expected standards of the day, the general UI got more minimalist while more colours were introduced (older versions looked darker). Despite the move towards a more modern UI in general, it is still possible for application developers to apply their own style. A typical result of this support was that developers of older applications did not bother updating their styles to the latest version (this is basically an XML file).

What we ended up with is a FIAT 127 in 2015's motorshow.

The problem with this situation is that not only we have to sometimes use outdated applications, but Google is also pushing a new 'UI language'. There is nothing wrong in having a new UI language...except when few developers are following it, and you're not one of them. If Android is to have a uniform, clean and modern UI, there should be a mechanism which automates the transition of styles to the latest standard in cases where the default file was left lying around. Automation is not uncommon on the Android ecosystem - Code is checked for potential errors, style files must be up to standard, even copyright issues are flagged by a bot - so why not a simple style file?

|

| Not quite in the same league |

As I mentioned earlier, there is also another problem which Google does not seem to want to fix - Material Design. Consistency is key in product branding and Google is/was known for their efforts in this regard. The ubiquitous bar in all their web products and their logo in the exact same location made it clear that this is a Google product.

Nowadays, their Android apps are cacophony of UI element styles and whatnot. Despite their efforts to make Material Design the next standard, it's already been 2 years and I have no idea when this next will be now. It can be seen in some apps, such as the settings, and the major Google apps. However, applications such as the Google Analytics still sport the Android 4.3 UI. Even worse is the app for Blogger - with UI probably designed by the Romans.

Yet again, even though the apps follow the general material design, all of them seem to have a language of their own. One aspect which was recently highlighted was the lack of consistent scrollbars. Now we got a new scrollbar in the application launcher too, for diversity.

Google Calender app has to be one of my favourites. It's fast, visually appealing and above all, useful. I use it regularly to set appointments, reminders, etc. just like all other users. The problem with the whole Calendar ecosystem is the web version. Why has Google introduced the Material Design, implemented it correctly in Calender on Android yet left the web version in the dark while at the same time it developed the Inbox service with correct material guidelines on both Android and the web (I'm not discussing whether Inbox is practical or not)? I understand the drive towards mobile and I truly appreciate the improved UI on mobile, but I'm not in favour of sheer inconsistency (and then again, there are web versions better than their apps).

Yes this was quite a rant - not really helpful for many. But it gets frustrating when you're working on your services and try to follow as many guidelines as possible to make your users happy. Thankfully apps are not accepted or rejected based on their looks and interaction, although sometimes I do favour such a system as it does improve the users' mobile experience.

Yet again, even though the apps follow the general material design, all of them seem to have a language of their own. One aspect which was recently highlighted was the lack of consistent scrollbars. Now we got a new scrollbar in the application launcher too, for diversity.

Google Calender app has to be one of my favourites. It's fast, visually appealing and above all, useful. I use it regularly to set appointments, reminders, etc. just like all other users. The problem with the whole Calendar ecosystem is the web version. Why has Google introduced the Material Design, implemented it correctly in Calender on Android yet left the web version in the dark while at the same time it developed the Inbox service with correct material guidelines on both Android and the web (I'm not discussing whether Inbox is practical or not)? I understand the drive towards mobile and I truly appreciate the improved UI on mobile, but I'm not in favour of sheer inconsistency (and then again, there are web versions better than their apps).

Yes this was quite a rant - not really helpful for many. But it gets frustrating when you're working on your services and try to follow as many guidelines as possible to make your users happy. Thankfully apps are not accepted or rejected based on their looks and interaction, although sometimes I do favour such a system as it does improve the users' mobile experience.